Origins of my Educator’s Edge: When I was a sophomore at a Department of Defense high school in Germany, I struggled with geometry. My brain hadn’t fully developed to make abstraction and spatial reasoning easy. Plus, I’d had a lousy experience with an algebra teacher who’d repeatedly made fun of my name. Let’s just say, I didn’t enter geometry with a can-do attitude.

When I talked to a school counselor about my struggles, this counselor suggested I take bookkeeping instead of geometry to meet my high school math requirements. This took me out of the college-bound track. I didn’t take the SATs or enroll in a world language, which is a requirement for most college admissions. Don’t get me wrong. I enjoyed my career-prep courses like typing and bookkeeping. I also had memorable, enriching experiences like participating in student leadership, journalism, cheerleading, and other clubs. I was busy learning about what’s possible but still had no idea what kind of scholar lay dormant inside of me. I am certain there were and are many students who share a similar academic history.

Like many teachers, my own experience fueled my passion for showing students what lies beyond the walls of a school. When I taught grade-level junior English in Seattle, I infused advanced placement material into the curriculum. I told students that I thought they were capable, and I witnessed students exceeding their own expectations. In addition, with the support of my principal, I offered a dozen evening AP Language and Composition sessions, which inspired The Uncommon AP Club. This novel is pure fiction but having witnessed students showing up for themselves and proving how scholarly they could be inspired the plot.

The Inevitability of Tracking

Back in the early 1990s, I had maybe two years of teaching under my belt when a new superintendent was hired in our school district. One of his philosophies was that advanced placement courses ought to be open for students rather than based on teacher permission.

Naïvely optimistic, I presented at an advanced placement (AP) parent night, whispering into the microphone, “If you build it, they will come,” borrowing a line from Field of Dreams (1989). And like the ghosts of baseball’s past, juniors flocked to AP Language and Composition. I was swinging for the fences as I encouraged students to register for this course. Enrollment surged from 18 students to at least 90, and I felt like I was running a victory lap around the bases. Yet, some of my colleagues weren’t playing for the same team.

Then, ten years later, I became an assistant principal and learned how complex a high school system can be, particularly a master schedule. I understood why some of my colleagues weren’t in favor of open-AP enrollment.

What I didn’t know as a teacher back in the early 1990s was that I had coaxed 90 academically motivated students from approximately 270 juniors, with the remaining 180 juniors in the grade-level junior English classes.

Here’s what the veteran teachers knew: In every course section (one period in the master schedule grid), it’s best to have a blend of students so that there’s a critical mass that has brought their readiness to learn each day. When a critical mass of students takes out their notebook and pen or pencil, pays attention in class, and asks interesting questions, it elevates all students’ learning. There’s an academic buzz and it’s contagious. Apathy can be equally as contagious.

Despite knowing this, would you rather gatekeep students from advanced placement courses or track even more students by allowing them into more challenging classes? It’s a hard question.

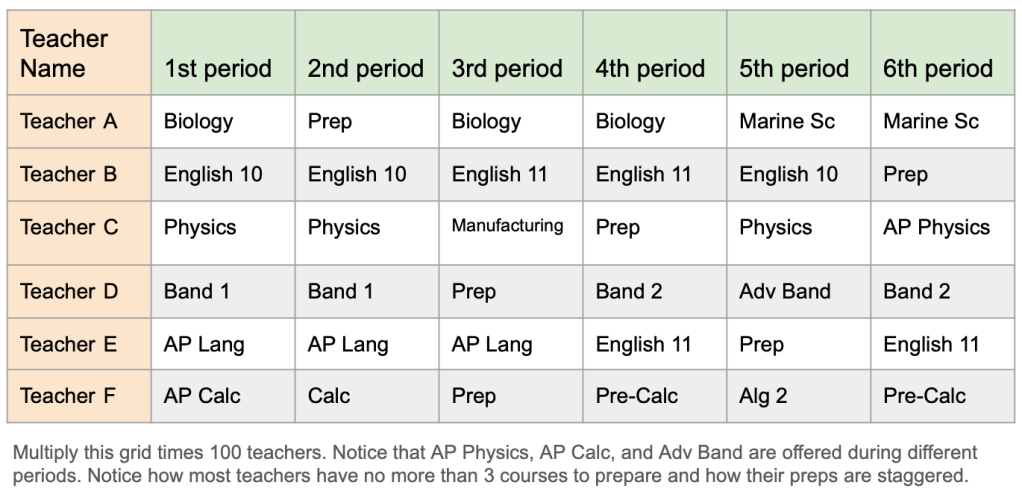

When building a master schedule, like sand art (image: Sand Art) that sloshes back and forth creating a different scene each time, achieving the perfect blend of courses and student enrollment requires hours of Tetris-like maneuvers. For example, if we move Teacher A’s Biology away from 3rd period, we must move a different sophomore course to 3rd period to ensure there are enough seats for every sophomore. If I explained this entire process, you’d probably get a headache from reading it all. Suffice to say that when I increased enrollment in AP, I threw off a delicate balance.

Even without a naïve teacher like me, building a master schedule that blends students effectively is challenging. Here’s why. Most high schools have specific, higher-level courses, such as AP physics or AP calculus with maybe 30 students in each. When a computer algorithm drops those 30 students into their selected courses, it tends to link them together. An orchestra or advanced band class can make the link even stronger. If students register for advanced band and AP physics, these courses need to be scheduled during different periods, increasing the likelihood that these students will have several classes together. This is tracking, though not intentionally.

Student Discovery in Limited Time

No matter how many interests surveys a teenager takes, learning about their aptitudes and preferences by trial and error is part of the high school experience. Registering for the right courses is overwhelming and, for some students who have their eye on specific universities or vocational certifications, planning is key.

There have been countless seniors who needed to change their course registration because they’d learned about prerequisites for post-high-school opportunities. In addition, the job market shifts or admissions requirements change, and flexibility is inevitable.

In The Uncommon AP Club, characters discover in real time what they want their futures to look like, which mirrors many students’ high school experiences. Some, like my sister, know their path since childhood. Karen asked for a nurse’s kit for Christmas when she was five, dispensing tiny candy pills to my brother, Dennis, and me and holding her plastic stethoscope to our hearts. (Our youngest brother, Len, was an infant back then.) Karen set herself on a college track before hitting puberty. Dennis was always curious about how things worked and was incredibly talented building things in his high school shop class. He became a drafting engineer via vocational training.

Schools are shifting into offering more technical pathways (aka tracks) because university educations have become extraordinarily expensive and college graduates aren’t guaranteed employment in the current marketplace. There’s a need for trades-skilled people and students are discovering their talent for creating, building, and fixing things thanks to supportive teachers and counselors.

Ideally, shouldn’t every student explore all their aptitudes and not run into barriers or detours like I did? Yet, there’re limited resources (courses and funding) and limited time. I found my inner scholar at a community college and eventually earned a master’s in education leadership.

The Uncommon AP Club is a tribute to students who keep seeking their passions and, when they find them, are unstoppable.

To subscribe to these blogs, hover near the lower right corner, and click subscribe.The tool looks like this:

Leave a comment